Dr. Caroline Cauchi Smailes is a novelist, scriptwriter, and academic. Her debut novel, In Search of Adam, was published in 2007 and since then, she has written seven additional novels, including international bestseller Like Bees To Honey and the experimental digital novel 99 Reasons Why.

Her novel The Drowning of Arthur Braxton was adapted into a feature film that premiered at the Raindance Film Festival in 2021, where it won Best UK Feature. In addition to her writing, Caroline has co-authored a short story collection and written scripts for short films and a musical called The Colour of Light.

Her current academic research focuses on how women involved in creative pursuits have been excluded from historical narratives and how they are being reimagined in contemporary creative practice. Caroline is also head of book editing at BubbleCow and is currently the Royal Literary Fund Fellow at Liverpool University.

Hi Caroline, welcome to Famous Writing Routines, great to have you here with us today! Your debut novel, In Search of Adam, was highly praised, and you’ve since written eight additional novels, including The Drowning of Arthur Braxton, which was recently adapted into a feature film. What inspired you to pursue writing, and how has your writing evolved over the years?

I guess that, for me, my need to write is rooted in a gnawing feeling of something that had to be said. That sounds super pretentious, but I’d been silenced for too long, and the grief that inhabited that space motivated me. In 2005, I reached my ‘now or never’ moment, and chose to discover if I could be a published writer. I enrolled on a creative writing course and felt entirely exposed in doing so.

Workshopping and sharing my writing was terrifying. Somehow though – and for reasons that were seemingly beyond my personality type – I trusted my creativity and worked hard. My debut was published two years later. Since then, and when reflecting, I’d say that drive has shifted away from self-focus and now I seek to give voice to those who’ve been erased or compromised – typically in terms of gender, social class, or regional voice. My writing’s evolved over the last eighteen years, but ‘being heard’ persists.

Your research centers on women who have been excluded from historical narratives, and you explore these themes in your creative writing. What motivated you to focus on these topics, and how has your research influenced your writing?

It’s fair to say that my creative and critical worlds collide in my research. As an academic, I became fascinated by the wider questions of the ways women involved in creative pursuits disappeared from historical narratives, and how they were being reimagined in contemporary creative practice.

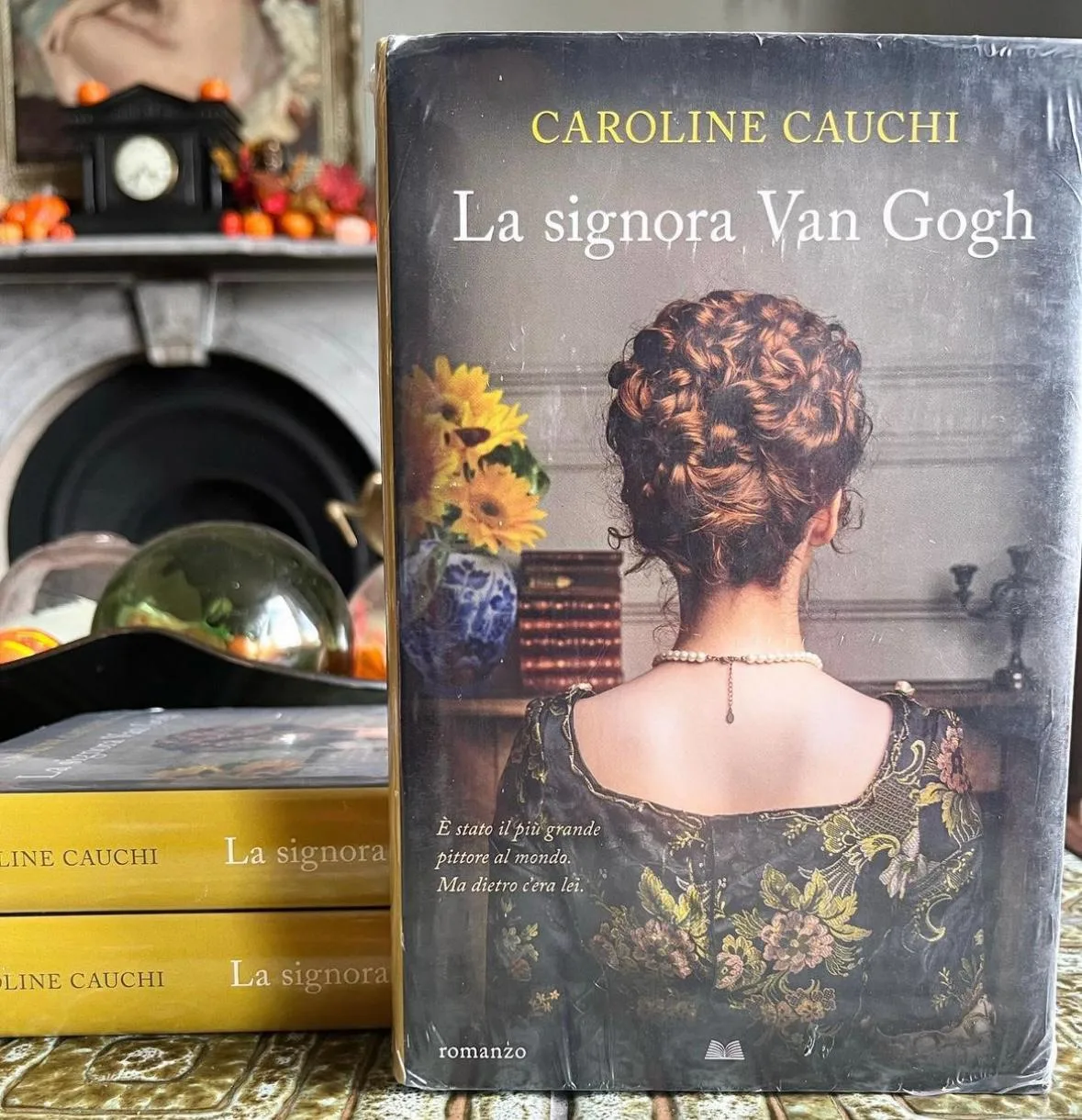

I measured gatekeepers’ functions in the lives of creative women throughout time and found many caretakers who either deliberately or inadvertently excluded or erased creative women, often simply by privileging those men around them. This captivated me. My creative response was to write a fictionalised account of the life of Johanna Van Gogh-Bonger (Mrs Van Gogh), showing what could be done to allow erased women to be both rewritten into historical narratives and to be viewed as equal to creative men.

In it, I tried to reconstruct her historical epoch by redefining a once-disappeared creative woman, whose rich life as an artist’s sister-in-law and art dealer’s wife overshadowed her key contribution to the reputation-building she undertook for the van Gogh family. Basically, the aim of my project was to further extend feminist scholarship and conversation, and I did that in the only way I could – I wrote a novel.

As someone who has worked on a variety of creative projects, from writing short stories and scripts to co-authoring a collection and writing a musical, can you tell us more about your creative process, and how you approach writing for different mediums?

Someone once described me as ‘genre fluid’ and I was never quite sure if that was a compliment. For me, the creative process results in a medium that best suits the narrative. I adapt, learn, and often throw tantrums, in an attempt to fit the storytelling with whatever form it commands. I’ve had varied success and a vast number of failures too.

I admire short story writers and the collection I co-authored (Freaks!) combined both flash and short story. It had a theme – superpowers – so each of my stories had the seed in a modern/less obvious take on having a ‘power’. The writing process was much quicker than my novel writing, and possibly the variation meant it allowed for more freedom.

The collection was illustrated, which offered additional depth and interpretation of the fiction. Collaborating with an artist and another writer was very different from the usual solitary stance of being a novelist. Writing a musical was challenging too. I’m obsessed with musical theatre – I have a spreadsheet that ranks every show watched in relation to costume, staging, script and music – so being asked to write the book for a musical was a dream role.

The music and lyrics were already written, so my challenge was to write a script around that and within six weeks. The creative process was a mix of the ridiculous, chaotic, and glorious. The show (The Colour of Light) sold out in both performances, but then the UK lockdowns for COVID-19 struck. My love of writing prose is firmly locked in writing dialogue, so writing scripts is something I’d like to explore a little more in the future. I’d love to write for radio and I’m even thinking about taking a course.

You use various pen names for your novels, including Caroline Smailes, Caroline Wallace, and Caroline Cauchi. Can you explain the reasoning behind this, and how do you approach developing a unique voice and style for each of your pen names?

This is a topic that causes much debate amongst my writer friends. Many can’t understand why I’d dilute my audience with three names. My reasoning links to the ‘genre fluid’ comment. My reputation as an ‘arch-experimentalist’ was established when The Observer linked me to Will Self and being experimental with form.

This is because, as Caroline Smailes, I wrote a digital novel with eleven endings (99 Reasons Why). It was one of the first novels to utilise technology in storytelling. Additionally, I used fonts and white space, or defied tropes and genre expectations in my first six novels. I loved experimenting with storytelling, but it did mean that when I decided to write commercial fiction, there were concerns about reader expectations for a novel by ‘Caroline Smailes’.

That’s when Caroline Wallace stepped forward and The Finding of Martha Lost was published. It signalled to readers that I was writing something entirely different. I returned to Caroline Smailes for novel eight (as it was experimental in format), but more recently I’ve written historical fiction.

The decision to use Caroline Cauchi (Mrs Van Gogh) was again to signal that new genre. My pen names are never hidden, and I think my next two novels will both be historical fiction – so Caroline Cauchi should be around for a little longer. Basically, I’m a nightmare to market or even my reading tastes are eclectic, and I write the novels that I’d like to read.

Can you tell us about your writing routine? What does a typical day look like for you?

I’m a Senior Lecturer in Prose at Liverpool John Moores University and this means that my ‘typical day’ alters, depending on where we are in the academic year. For two semesters of the year, I teach students and during that time – mid-September to mid-April – my writing is a tiny word count every day, as well as research and plotting.

Then from mid-April to mid-September, writing is my priority and I’ll complete a first draft. I’ve found that I work best when I have limited time, so I’m at my desk from 8 a.m. until 11:30 a.m. The last half hour is spent writing bullet points for the next day’s session. I always leave my writing knowing what I’ll write next. The rest of the day is spent on other creative projects, university work or academic research. I work best when I make myself stop writing. I guess that sounds counterintuitive, but it leaves me excited for the next day.

If you could have a conversation with any author throughout history about their writing routine and creative process, who would that person be?

Roald Dahl or John Fowles.

I’d love to know about the books you’re reading at the moment. What have been some of your favourite recent reads?

As I’m researching, plotting and finding the right first person voice, I’m currently only reading non-fiction. I’ve recently devoured The Story of Art Without Men (Katy Hessel), Landlines (Raynor Winn) and Wild (Amy Jeffs). Each unique, all are remarkable.

As the head of book editing at BubbleCow and the Royal Literary Fund Fellow at Liverpool University, you provide support and guidance to other writers. What advice do you have for aspiring writers, and what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced as a writer and editor?

I’m possibly projecting or simply talking about me, but many novelists are pretty talented in avoiding writing. Whether that be a ‘quick five minutes’ on social media that spirals into two hours, or convincing ourselves that we’re ‘researching’ when really we’re dodging writing. My advice surrounds the ways we give ourselves permission NOT to write.

Some need their writing space to be a certain temperature, or to have a bottle of wine that’s chilled, or twenty cigarettes and a specific ashtray, or silence, or a baby crying, or a special pen – and each and every excuse takes us away from doing what writers actually need to do. We need to write. So, I’d urge aspiring writers to set tiny word targets that they’ll smash each day. Large word counts often set writers up to fail, just as a wish list of those ‘ideal conditions’ will offer permission not to get on with the task.

As for the biggest challenges I’ve faced as a writer and editor? I think that the voices and excuses I tell myself have led to my biggest hurdles in writing. I’ve had periods of not writing – sometimes for a full year. Life gets in the way of creativity and, as a writer, there’s a need to be a little kinder about both those expectations and excuses.

Also, if I’m being entirely honest, some days I find it hard to juggle writing, academic jobs, my home life and being an editor. Those days it all feels too much. I’ve learned though, that emotions and stresses pass, but my need to write or to edit persists. The simple fact is that I only feel like a writer when I actually write. And I’m a better writer because I edit. That all feeds into how I teach too. It’s one big, fragile, circle of creativity.

What does your current writing workspace look like?

In progress! We recently bought an old, Victorian house that we’re renovating. Eventually, I’ll have an office in the attic, and I’ve plans to make it into a nest. For now though, I write in a (recently renovated) room downstairs, next to huge bookcases that require a ladder to reach the top shelves. The house overlooks a river and has been ridiculously cold, but this room has an open fire and writing in here makes me feel like a – possibly stereotypical – Victorian novelist.